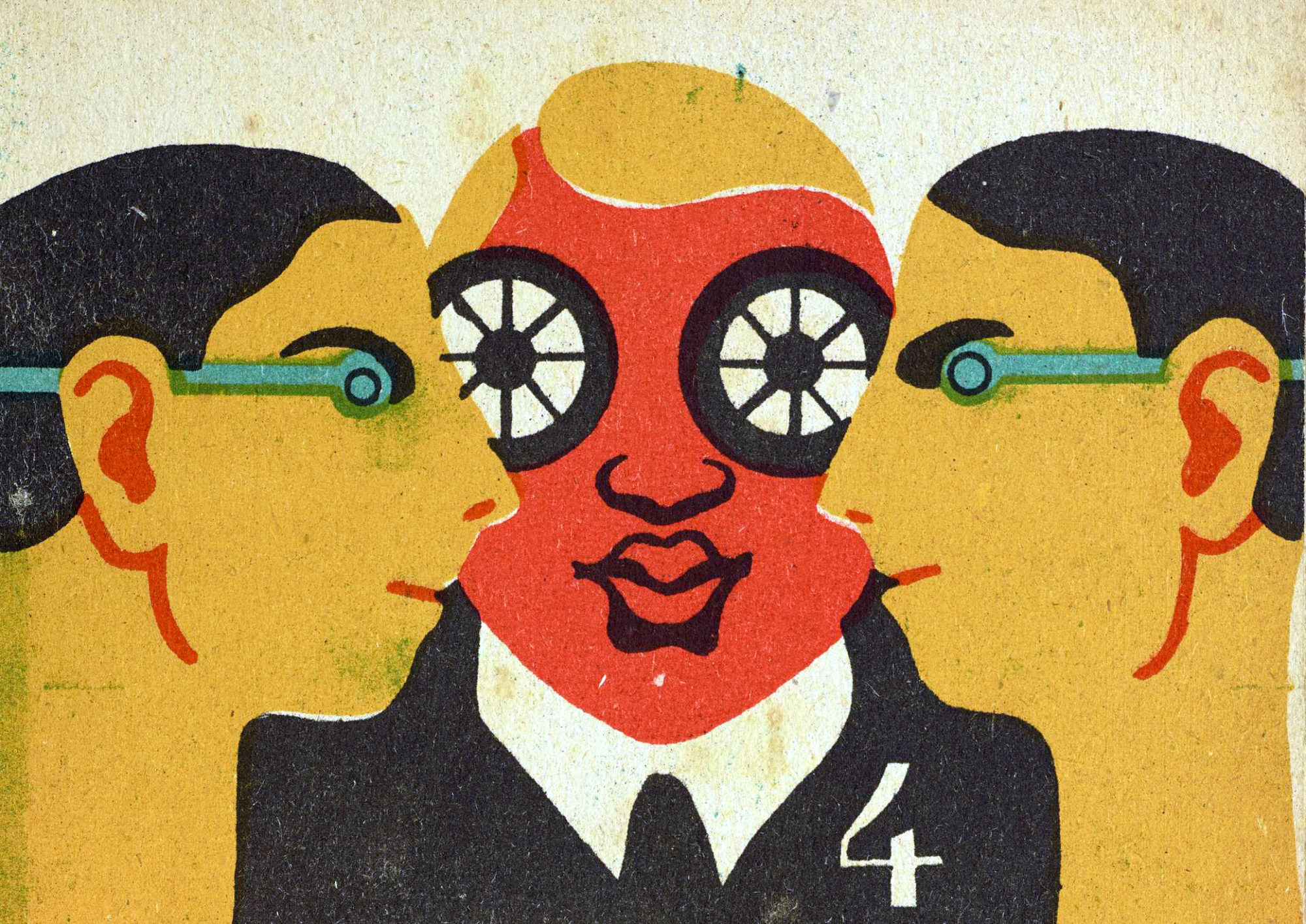

Nikolai Smirnov’s 1927 children’s book Dlia chego krasnaia armiia features two boys, Ivan and Stepan, who observe the Red Army marching, defending their socialist motherland in trenches, flying airplanes, working telephones, firing a howitzer, riding in the cavalry, driving motorcycles, fighting in tanks, dispensing gas, wearing gas masks, shining floodlights, and standing guard. Throughout the tale, Ivan and Stepan ask questions of each other, drawing the young reader into the story. Smirnov’s story therefore narrates the role the Red Army plays in defending the Soviet motherland but also makes army work appear to be fun and exciting. Accompanied by lively, visually arresting illustrations by Galina and Ol’ga Chichagova along with bold words that help young readers learn the Red Army’s jobs (“KONNITSA,” for example, with a picture of four soldiers on horseback), the story concludes with a Red Army commander encouraging the boys to learn that the Red Army exists for them and that they too can aspire to be part of it. As he notes, however, the actual Red Army is not a game, for its soldiers must defend the country, its workers, and peasants. At home, however, the boys could play at soldiers. After observing the Red Army in action, the book concludes that “when they [Ivan and Stepan]  played Red Army, they knew what the Red Army was needed for and how it worked.”

played Red Army, they knew what the Red Army was needed for and how it worked.”

Smirnov’s story highlights a theme that appears in several early Soviet children’s books: namely, how good Soviet children are encouraged to play soldiers and in doing so, to understand the Red Army’s defense of the socialist motherland. In addition to Smirnov’s story, my article will focus on a handful of Soviet children’s books that depict the Red Army as a source for serious fun: Valerian Shcheglov’s 1928 Krasnoarmeets Vaniushka, Aleksandr Deneika’s 1929 Krasnaia armiia, Deneika’s 1930 Parad krasnoi armii, and Arkadi Gaidar’s 1933 Skazka o voennoi taine o mal’chishe-kibal’chishe i ego tverdom slove all encouraged young Soviet readers to see themselves as soldiers and see army work as a source for play.