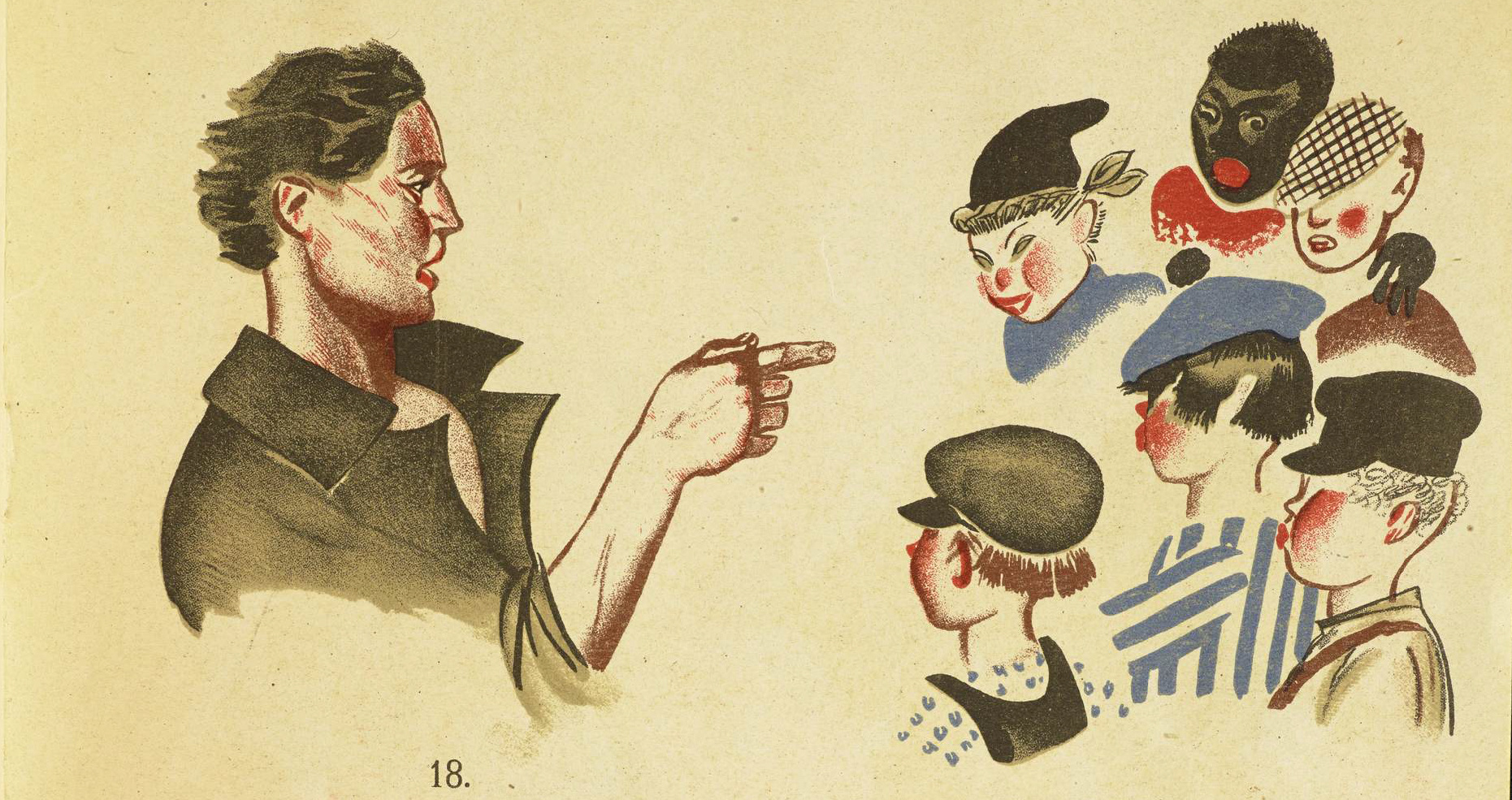

How can a fixed image invite children to animate objects, and what role do such animations play in socializing young children into socialist institutions and ideals of communism? On the first page of Sergei Rozanov’s Vanya’s kindergarten: a little play for children (Vanin detskiĭ sad : pʹeska dli︠a︡ deteĭ, 1928), Petrushka holds hero Vanya by the ear, his head cocked sideways, his body dangling at a 45-degree angle below, amidst the white of the page that also serves as an imagined curtain for Petrushka’s fairground booth.

Professional puppet troupes played an important role in socializing young Soviet children, but Soviet children’s books also invited children to become the animators. I will consider how such books and their use of illustrations to encourage children – on the one hand, to construct, literally, these objects – and, on the other hand, to create, through children’s animation of such objects. Art historians have highlighted early Soviet ideals of creating “dynamic” objects that would incorporate production into everyday activities (Arvatov 1997, Kiaer 2005). Historians of childhood have noted pedagogues’ deliberate conflation of work and play in kindergartens, merging creativity and productivity (Kirschenbaum 2001).

Books that motivate children (and supervising adults) to create toys thus incorporate children into the production of play. This paper will analyze the role of visual depictions of objects in inviting creation and animation, whether through their decontextualization, through details emphasizing their status as objects (that could become social subjects), or by other means.