In her article “The End of Empire? Colonial and Postcolonial Journeys in Children’s Books,” Australian scholar Clare Bradford asserts that “to read children’s books of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is to read texts produced within a pattern of imperial culture” (Bradford 196). Using texts written about “the far reaches of the British Empire,” Bradford comments on how the lands and indigenous peoples “out there” are othered in order to produce and sustain an idea fundamental to colonial discourse: that “Europe … is the norm by which other countries and peoples are judged” (Bradford 197). In my investigation of 1920s and 1930s Soviet children’s literature, I would like to address similar practices that became the foundation for both verbal and pictorial discourses developed for the new generation of Soviet citizens.

In her article “The End of Empire? Colonial and Postcolonial Journeys in Children’s Books,” Australian scholar Clare Bradford asserts that “to read children’s books of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is to read texts produced within a pattern of imperial culture” (Bradford 196). Using texts written about “the far reaches of the British Empire,” Bradford comments on how the lands and indigenous peoples “out there” are othered in order to produce and sustain an idea fundamental to colonial discourse: that “Europe … is the norm by which other countries and peoples are judged” (Bradford 197). In my investigation of 1920s and 1930s Soviet children’s literature, I would like to address similar practices that became the foundation for both verbal and pictorial discourses developed for the new generation of Soviet citizens.

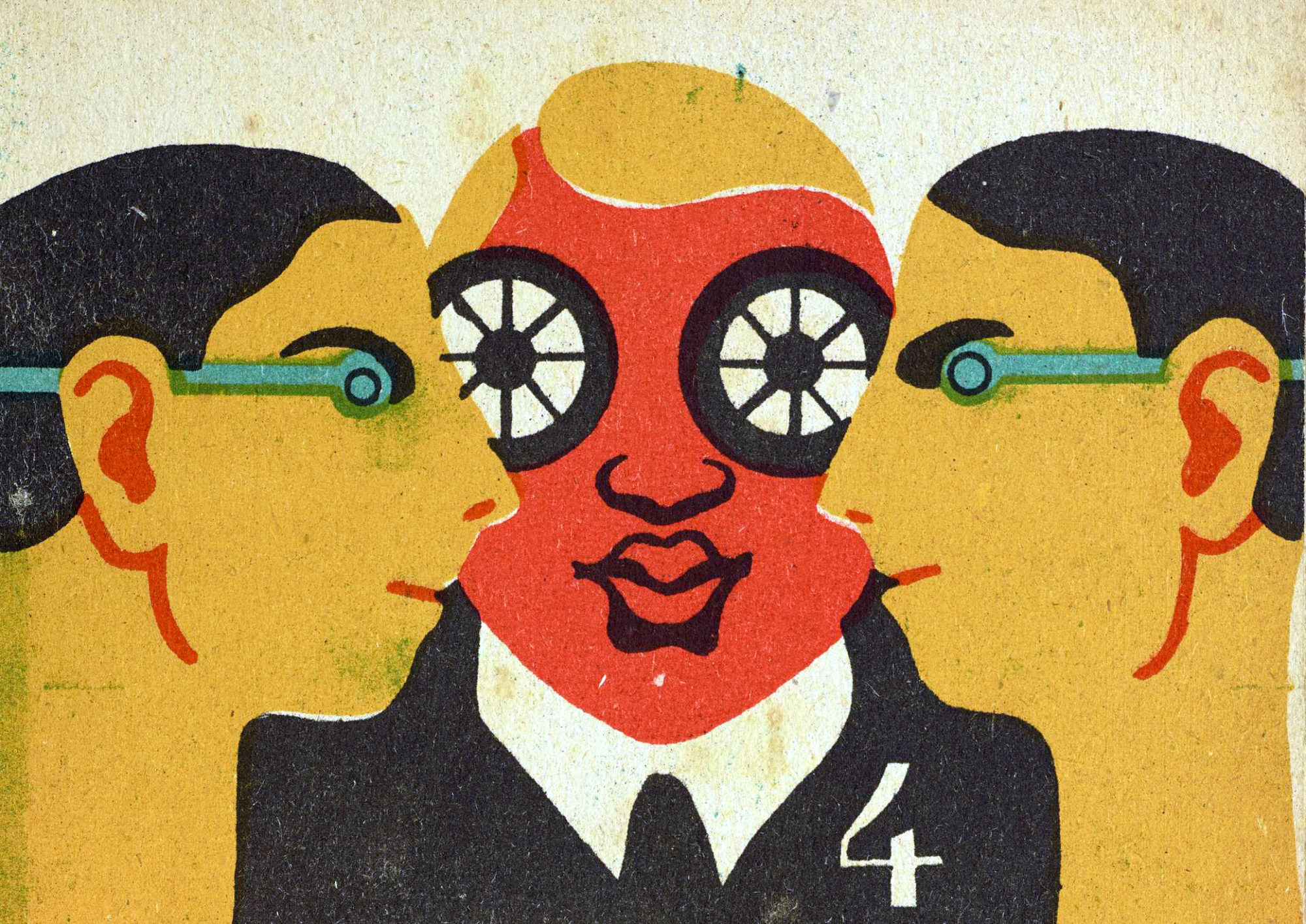

Proletarian internationalism that, next to collectivism and class solidarity, formed the core of new communist pedagogical doctrine was best expressed through the creation of interknizhki – richly illustrated picture books dedicated to the depiction of troubled children’s lives outside of Soviet Russia. I intend to demonstrate how the visual image in the 1920s interknizhki overpowered the textual narrative, thus creating a certain imbalance between the verbal and the visual message. While the entertainment value of children’s literature remained the essential element in the creation of the new narrative, the power of the visual image, with its creative superiority over the simplified text, led to the attention being shifted from the ideologically  correct verbal message to the engagingly detailed exotic picture of foreign surroundings.

correct verbal message to the engagingly detailed exotic picture of foreign surroundings.

The discord that was created through such divergence resulted in an altering of the original ideological task that both the author and the illustrator were charged with. The new revolutionary language of proletarian unity and equality was absorbed by traditional colonial images of the subaltern – references to skin color, nakedness, attraction to cheap and flashy baubles. Was such deviation intentional or was this phenomenon the result of palimpsest modality in which many texts in post-revolutionary children’s literature in Soviet Russia were composed? Or was this practice the result of a claim by many contemporary scholars about children’s literature being “the free zone of artistic expression and experimentation” (Marietta Chudakova, Igor’ Kondakov)? While both assertions should not be ignored, I believe that the visual language of interknizhki demonstrates the very process of formation of the socialist visual vocabulary that later was successfully adopted in Soviet public art for adults (posters, political caricatures etc.) I propose to explore this discord between the narrative and its casting in image and focus on the ways the idioms of proletarian internationalism were transmitted into children’s literature of the 1920s-1930s.